Cheesemaking is a craft and one that requires plenty of expertise, along with great dexterity and precision. It is a craft in which many things are still done exactly as they were many centuries ago. Here we introduce you to the nine steps of cheesemaking and, in doing so, tell you a little bit about the history of Switzerland.

The basic ingredient: milk

Cheeses from Switzerland are produced from fresh milk, which is supplied by farmers to the creameries twice a day. The properties of this milk are partly responsible for the final character of the cheese.

There are over 700 varieties of Swiss cheese, but they all have one thing in common: their production starts with Swiss milk. The vast majority of the cheese is made using cow’s milk. Farmers tend to supply their creamery with fresh, low-germ milk from healthy animals twice each day. This single raw material is then used to produce a huge variety of different cheeses. There are so many different factors – including animal breed, feed, climate, milk fat content, different bacteria cultures, type of maturation and treatment – that lend each and every wheel of cheese its individual character.

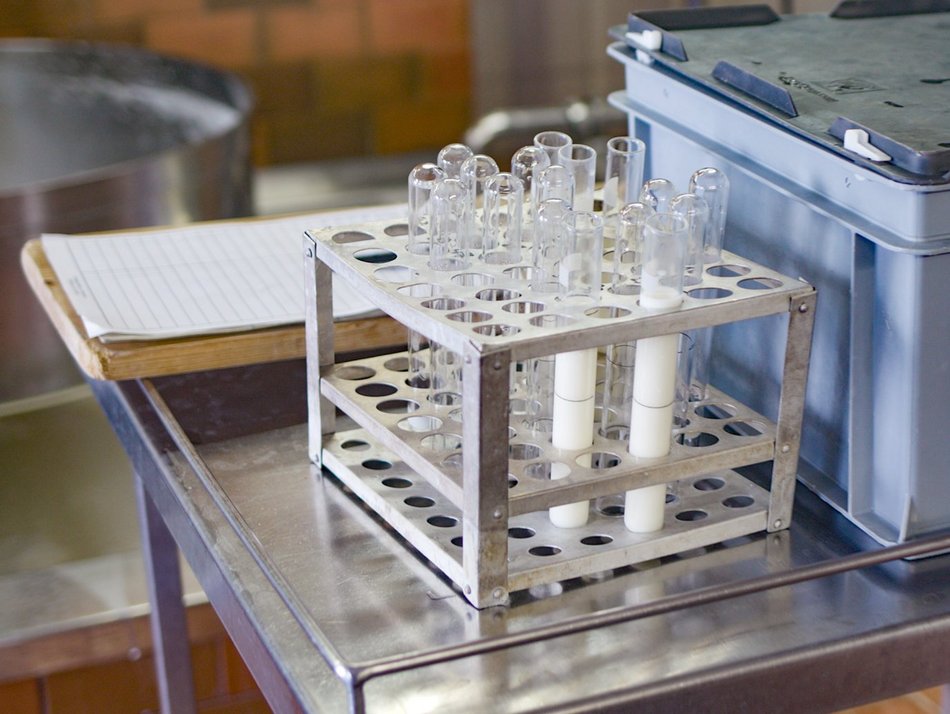

Milk selection and milk handling

Upon delivery, the milk is first tested for its quality and then filtered. Unpasteurised milk is tested rigorously – if no unpasteurised cheese is to be produced, the milk is gently thermised or pasteurised.

First, the milk is tested for its bacteriological and sensory condition. The following criteria are considered:

- The number of cells provides information about the udder health of the animals.

- The microbial count provides information about the hygiene of the milking and the milk.

- Inhibitors show whether the dairy cattle have been treated with antibiotics.

- The freezing point indicates the possibility of the milk having been diluted.

The creameries safeguard the production of unpasteurised milk through further tests specific to each creamery. Unless the milk is being used to produce genuine unpasteurised cheese, the milk is gently heated to produce thermised (warmed to 63°C) or pasteurised milk (warmed to at least 72°C).

Curdling the milk

The milk is poured into the vat and stirred as it is gradually heated. The lactic acid bacteria and rennet are then added to begin the coagulation process. This curdling results in a gelatinous substance.

The milk in the “cheese vat” is now gently heated up to 30°-32°C. The cheesemaker will then add special lactic acid bacteria cultures and the rennet. Adding the cultures increases the acidity in the milk, which increases the effect of the rennet. The milk is then left to stand for 35-40 minutes. Within this time, the rennet curdles the milk – the so-called curdling process. The cheese vat now contains curd: a smooth, pudding-like solid that awaits further processing.

In order to produce the famous AOP cheeses from Switzerland, bacteria are used that were naturally present in milk some 40 year ago and have since been cultivated by Agroscope Liebefeld-Posieux and can be sourced by the creameries from there as microbial strains.

Rennet can be sourced from the stomach lining of young calves (as well as young goats or lamb stomachs), from special bacteria cultures (microbial) or – rarely – from plants (for example, cardoon thistle or solanum dobium) and is used in liquid, powder or paste form. Genetically modified rennet is not used in Switzerland.

Just a few grams of rennet are all that is required to curdle around 1,000 litres of milk. But rennet does not just curdle the milk; it also helps the cheese to mature before it is eaten.

Tip: check out the Cheesefinder to find the latest Swiss cheeses that don’t contain animal rennet.

Curd processing

Now the cheese harp is introduced: it is used to cut the curd into small pieces. These pieces of curd determine the type of cheese they will become – the smaller the pieces, the harder the final cheese will be.

As soon as the curd has reached the required consistency, it is cut with a cheese harp. A cheese harp may feature wires and/or blades, so that it can cut through the curd. The longer the cheese is stirred with the harp, the smaller the diameter of the small pieces of curd and the harder the final cheese will be. This is because the finer the curd, the less water there is in the cheese. This process varies for different types of cheese – as such, the cheesemaker must work with great precision here.

Pre-curdling

The curds are stirred and heated up – the harder the cheese is to be, the higher the temperature. Thus, the cheese becomes increasingly solid.

The curds are now stirred and gradually heated. The higher the desired water content for the cheese, the more it is heated (hard and extra-hard cheese is heated to approx. 51-58 °C, soft cheese to approx. 35 °C). Stirring and warming the curds causes the curd granules to contract and separate from the whey. The cheese solidifies.

Whey is actually a waste product from the cheesemaking process – it is the name given to the green liquid, which escapes from the curd as it is processed. The whey is pumped away and generally spun and then processed into other products. Whey products include whey drinks, whey butter and quark. It is also used in processed foods or cosmetics as whey powder. However, the majority of the whey is used as animal feed.

Note: “Molke”, “Schotte” and “Sirte” are all names used for whey in Switzerland – “Molke” is the most common term in the German-speaking world.

Shaping and pressing

Once the desired solidity level has been reached, the cheese is poured into a mould. The holes in the base of the mould allow the whey to escape. In addition, the entire cheese is compressed to remove additional liquid.

As soon as the cheese has the right level of solidity, it is filled into perforated moulds together with the whey. The whey now drains off and the cheese mass remains in the mould. Cheese brands are applied straight away as a “cheese passport” for identification purposes. The lid of the mould is placed over the cheese and the cheese is compressed. This lends the cheese the desired shape and also helps to remove additional whey.

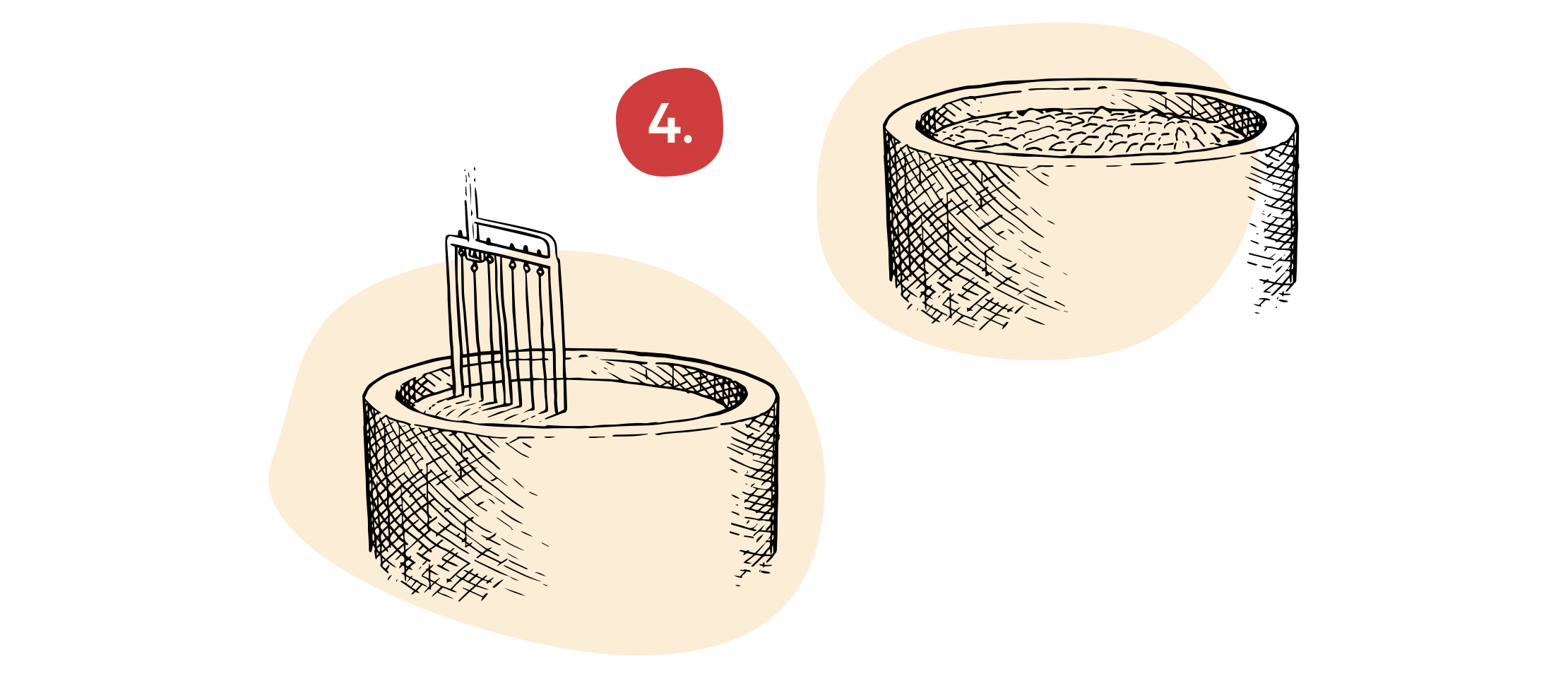

Brine bath

The brine bath is the next step: the floating cheese absorbs the salt and releases whey. The rind forms gradually and the flavour of the cheese becomes more intense.

Depending on the size of the cheese, it can be placed in a bath of brine for between a few hours and two days. The brine bath has a salt content of around 22% and a temperature of approx. 15 °C. The high salt content helps to remove more of the whey and the cheese also absorbs the salt. During this process, the cheese solidifies and a rind forms on the surface. This gives the cheese the protection it requires from external influences and helps to keep the shape of the cheese. The brine bath also prevents the formation of undesired bacteria on the surface. The absorption of the salt improves the taste of the cheese.

Interesting fact: the density of the brine of 1.15 kg / l means that the heavy wheels of cheese actually float in the brine bath.

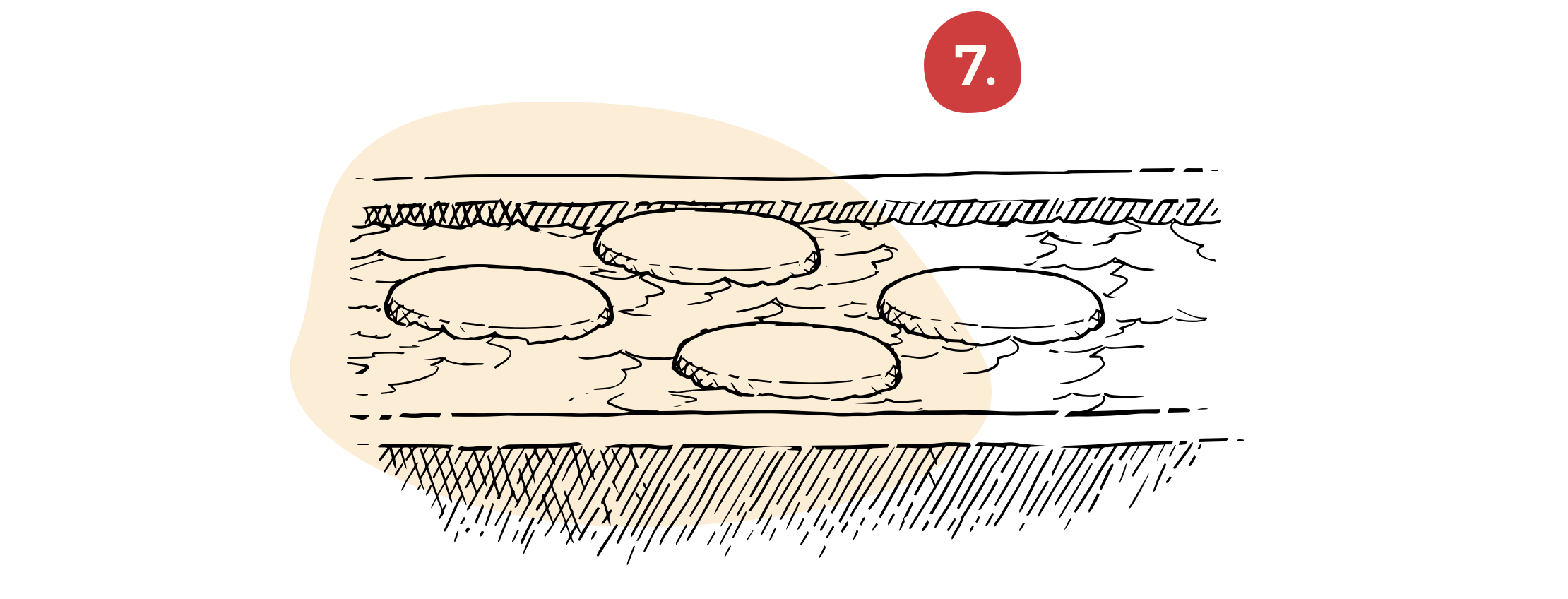

Maturation and affinage

The cheese undergoes several changes during maturation in the cellar: the rind develops, the inside of the cheese changes colour, holes are formed and the cheese solidifies. An affineur often refines the cheese by rubbing in herbs, cider or white wine.

The process continues in the cellar. Cheese maturation covers the entirety of the enzyme processes that take place in cheese. A rather tasteless, fresh protein is transformed into a soft, delicious cheese, bursting with character.

Cheese maturation leads to visual, chemical and microbiological changes in the cheese:

- the visual signs include the formation of an external rind, holes inside the cheese ((infobox)), a smooth cheese and changes in colour.

- Bio-chemical processes break down the protein into amino acids and lead to a change in the state of the cheese, making it easier to digest.

- Both microbiological influences and varying production methods can affect the formation of holes.

Maturation spans from a few days to several months or even years. During this time, the cheese turns into a solid. The maturation period depends on the variety and the size of the cheese, and is defined in product specifications and market regulations.

Cheese maturation is also known as affinage. An affineur adds the finishing touches to the cheese during maturation and only presents the cheese for sale when it has reached peak maturation. Special expertise is required to calculate this moment. The flavour of a cheese can also be enhanced through additional treatments with cider, white wine, special herbal brine etc. during this stage.

A popular topic and an issue that sparks all kinds of speculation: what are the holes in the cheese all about?

Gas-forming microorganisms create carbon dioxide, or CO2. In solid or viscous cheese, the CO2 cannot escape evenly and slowly out of the cheese. As a result, large, irregular holes are formed or cracks created in the places where there is a heavy concentration of gas.

The CO2 is distributed evenly in soft cheese. This means that a large, even hole can “grow” gradually in places where the curds have not grown together. CO2 creates good holes due to its high water solubility.

Et voilà! The mystery behind the holes in the cheese has been solved!

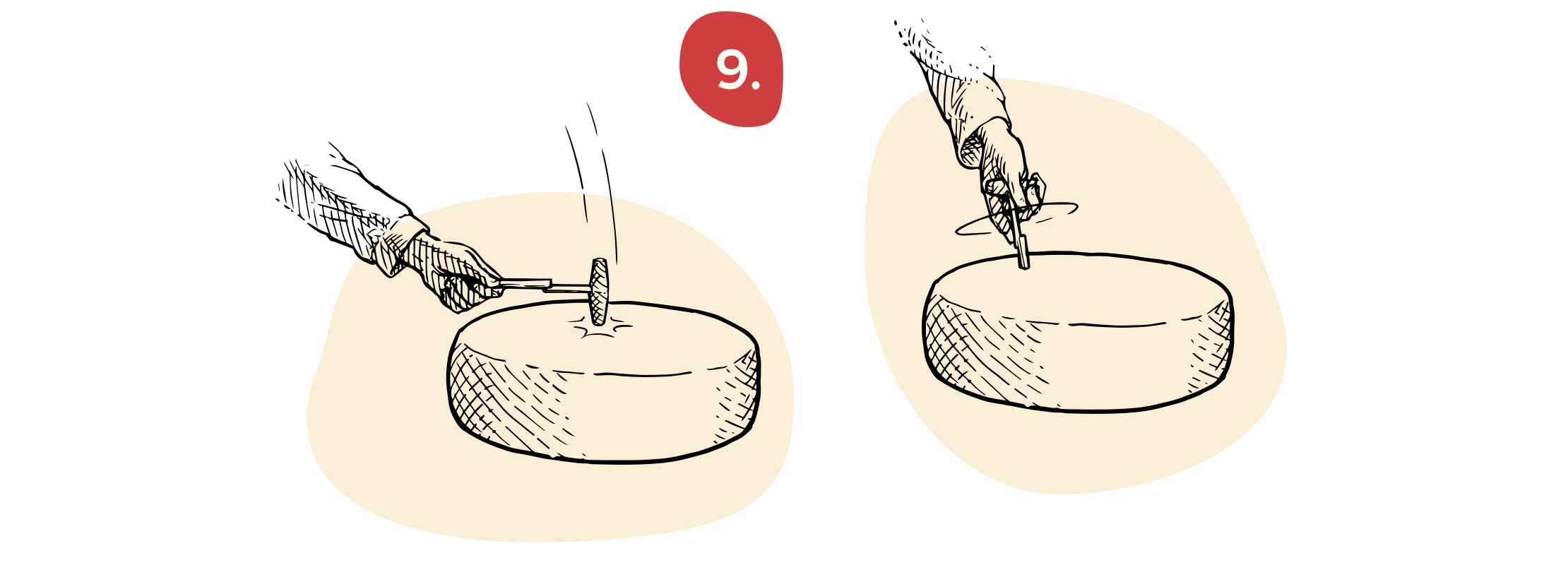

Quality control

The final step sees the cheese undergo various tests. They include inspections of the hole formation, the cheese quality, the taste and the external appearance. Then the cheese is ready to be sold.

Before the cheese is sold, it undergoes thorough testing. This ensures that only excellent quality cheese is sold. The formation of holes, the quality of the cheese, the taste and the external appearance (shape and preservation) are all inspected and assessed.

Прежде чем сыр поступит в продажу, его тщательно проверяют. Это гарантирует продажу сыра только высокого качества. Контролируются и оцениваются такие критерии как образование отверстий, качество сырного теста, вкус и внешний вид (форма и консервация)